A CHAPTER OF MISHAPS

My brother Desmond was born when I was a little over five and a half years old. My mother always insisted he arrived just after midnight on New Year's Eve. The doctor attending her, however, said it was earlier, so his official birthday was the 30th of December. I was not at home for this event. I knew nothing about it beforehand and cannot remember being told about it afterwards.

I suppose I may have been jealous of my baby brother but I certainly have no recollection of it. In fact, as I recall it today, I seem to have adopted a proprietary 'big sister' attitude towards him and for many years was a real bossyboots. After all, I had a five and a half years advantage over him!

Unfortunately, he was a very sickly baby. Mother was unable to breastfeed him and he was unable to digest any proprietary baby-food. My parents were in utter despair until one day Mother tried Nestles Milk - and it worked. Other doctors were at one in condemning this. But my father decided that in the circumstances, it was worth continuing as a temporary measure until the child was stronger. Once he was over the critical stage they would change tactics. And that also worked.

Our dog, Paddy, was another who, strangely, did not resent the baby. Mother used to put the child in his pram in the garden, and Paddy would stay and guard him. And 'guarding' meant an attitude of snarling and lips drawn back and a 'Don't you dare come a step nearer!' towards any stranger who showed signs of approaching the pram.

Whenever I was at home for holidays I was more than happy to spend time with my brother and was always trying to carry him around. On one occasion, when he was still very little, I remember, I tried to carry him downstairs - and dropped him. I was terrified. I was sure I had caused him irreparable damage. He wailed. I howled. But fortunately, he apparently suffered very little harm.

While he was still a baby he had a boil or some such thing on his head and my father decided it must be lanced immediately. Without more ado, the kitchen table was scrubbed down (and I mean scrubbed), and my father scrubbed up - and the job was done.

There was another occasion when Des was about two years old, when, inadvertently, I very nearly did cause him to be badly injured. My father used cut-throat razors. (No, thank goodness, there was no razor involved in this incident, but it was bad enough anyway). He also liked very hot water for shaving and it was usual for someone, either Mother or the maid, to bring him up a can of boiling water to the bathroom.

On that particular morning, I was in the kitchen when a kettleful of boiling water was poured into the can - a nice white enamel can with a spout - and I begged to be allowed to take it upstairs. For some reason, I got my own way. As I went out of the door, my little brother ran in, full tilt into me, and of course, the water splashed out on him. We both started screaming. Both my parents came running.

If one must have an accident I suppose a doctor's house is as good a place as any to suffer it. Des was wearing a very thick pullover and that took the worst of the hot water. Mother whipped it off him and he had the good fortune to get immediate first aid from both a doctor and a nurse. So there were no permanent ill effects.

I myself, at about the age of three, ran into a door and cut my lip badly. My father wanted to stitch it but the mere thought of that sent me into uncontrollable hysterics, to such a degree that he judged it better to leave it alone. I can still remember the feeling of acute terror conjured up in my mind by the word 'needle'. Furthermore, the horror remained with me and it was many, many years, even after I was an adult before I was able to be rational about it.

Another time, when I was about six, my cousins were staying with us and we had a fudge-making session. The fudge would be poured on to dishes and allowed to cool before being cut into pieces. But I was impatient, picked up a knife and plunged it into the fudge. Unfortunately, the knife slid across the dish and straight into my left hand. The sight of the blood was quite enough for me and off I went into hysterics again.

My mother did her best. She nursed me on her knee, bandaged my hand, talked sweet nothings to me, kissed the poor hand better, but it didn't work. Eventually (probably in desperation) she said: "You know, Leslie O'Brien will think you're a great big baby if you go on like this."

Leslie was an older boy who sometimes came to stay with his grandmother, quite close to Glamorgan House. I did not like him because his greatest delight was to tease. And his method of teasing was to slip spiders or slugs down one's back! Just the same, like him or not, I was not going to be thought a baby by him and, miraculously, my hysterics were a thing of the past!

There was an occasion when my four-year-old brother, not I this time, embarrassed my mother with his choice of words. She was having a bridge party that afternoon and friends had arrived. In came Des saying "Bugger, bugger, bugger!" Poor Mother remonstrated and got the reply, "Well, Sandy Beverly says bugger!"

"That's not the point," said Mother. "That's a naughty word and you mustn't say it."

Des retired to the hall and sat on the bottom step. What followed was a monologue which went like this:

"Bugger is a naughty word, so I mustn't say bugger, but Sandy Beverly says bugger, and Sandy Beverly is a naughty boy to say bugger because bugger is a naughty word, so..."

And so on and on and on. You would almost think he had learned it off by heart. Mother would have taken him to task again but Daddy told her to leave him alone and he would forget about it. He did.

Later on, he found another expression: "Damn and blood it!" I fancy that one was his own mixed up version of something overheard. He always knew where he had heard these things. On one occasion my father gave expression to his feelings about what another child had said, without realising that his son was within earshot. To my parents' horror, the next time Des saw the boy, he told him:

"My Daddy says he'd like to put you on a broomstick and shove you up the chimney!"

On the afternoon of Christmas Eve when Des was about two years old, he accidentally broke my doll. I suppose I was on a bit of a 'high' because of the approach of Christmas Day and such things are infectious. In a burst of excitement Des jumped on the chair on which I had left my china-headed doll, and of course, the worst happened. The doll bounced to the floor and lay there with a broken head.

Des was most upset about it. So was I, but on the other hand I was genuinely fond of my little brother and tried to hide my feelings. To my mother they must, nevertheless, have been abundantly clear. On Christmas morning, imagine my delight to find that Father Christmas had left me a new doll, identical to the broken one!

How Mother managed it I do not know for it was already tea time when the doll was broken. The new one had to be bought in Douglas - seven miles away - and the shops must already have been closing. But she was a very determined woman when she made up her mind.

Later on, she had a new head put on the old doll so then, of course, I had twins. I named them Joan and Marjorie after the very beautiful twin daughters of a friend of Mother's.

Embarrassments and mishaps within the family are one thing, but naturally, in the course of medical practice, any doctor may find himself having to cope with an accident or even a catastrophe situation. Casualty doctors in hospitals are obviously more likely to have such experiences but even in rural areas, these events can occur.

As I mentioned earlier, a Manx Electric Railway accident happened quite close to where we lived and my father was very distressed by the injuries.

There had much earlier been a nasty accident at the time when the lead mines were still in operation. A man got his arm caught in machinery and twisted off. Without fuss or bother he took to his heels and ran to the surgery in the village. The twisting acted as a tourniquet for long enough to enable him to get there safely and receive attention. Obviously, in those days, a man was undoubtedly a man!

Down in Old Laxey, a small child once ran out into the road in the path of a lorry. The driver swerved to avoid the toddler but was unable to avoid the mother who ran into the road after her child. Daddy suspected she had broken her back, which sadly, turned out to be only too true. He would not allow her to be moved in any way until the ambulance men arrived with the proper equipment. As a result, he found himself the object of much abuse by, no doubt well-meaning, but ignorant people.

Laxey, amongst other things, was a fishing village, and from time to time there would be small accidents. One such was when a lad had his hand caught on a fish hook. He came to the surgery with it still there. My father asked the police sergeant to come and help as the boy was nervous and he intended to put him out completely with an anaesthetic while he removed the hook.

Daddy was a qualified anaesthetist (he had in fact practised as such at an earlier time in Shrewsbury Hospital), but of course in those days anaesthetics were nothing like they are to-day. He warned the sergeant not to standnear the boy's feet as he would probably kick out. This is precisely what happened and the sergeant who had not taken the warning seriously, landed on his back on the floor. Daddy nearly had two patients instead of one.

One Sunday summer afternoon my father and I were at home alone when a girl and her boyfriend arrived at the house. They had been out for an afternoon walk and the girl had slipped when climbing over the gate to a field and cut her mouth badly. It had to be stitched. I remember boiling the water for sterilising and also how concerned my father was to do a good job. She was a pretty girl, he said, and he wanted to be sure she stayed that way.

Then there was the time that Billy Kneale, the farmer who supplied us with milk, brought a patient who had to be taken on to Noble's Hospital in Douglas. Billy was on his milk round with his horse and cart. People used to go out to meet him to collect their milk but on one occasion a poor woman had slipped and cut her hand and wrist very badly. Billy not being one to panic, promptly wrapped up her arm, got her into his cart and conveyed her hastily to our house.

Daddy was away at the time on a well earned holiday and we had a locum who was also a family friend. Tony, the locum, took the patient into the kitchen and proceeded to unwrap the arm. Unfortunately he had not realised how serious the injury was. The poor lady had cut an artery and as he removed the coverings, blood spurted out in typical cut artery fashion. Tony had to use a tourniquet and get the patient to hospital as fast as possible.

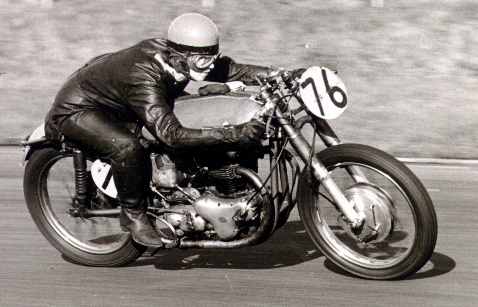

My father himself, had two nasty accidents. When we first went to live in the Isle of Man he used to ride a motorbike. This was very convenient for his practice which was a scattered one, stretching seven miles to Douglas in one direction and about ten miles to Ramsey in the other. Many of his patients lived on farms in out-of-the-way places and up in the hills, and for calls such as those the bike was ideal.

His first accident occurred when I was very small. He went out on a night call, rounded a bend in the road and ran into a cart which had been left there. He went straight over the handlebars and all but lost his nose. Fortunately the medics were able to stitch it back again but for the rest of his life he had a scar all down one side of it.

He was still riding the motorbike when he had his second accident. I was then ten years old. Mother and Des and I had been to Garwick beach for the afternoon. We had only just got home when the phone rang and someone was sympathising because of Daddy's accident. I can remember sitting on the stairs, trying to make out what had happened, my mother desperately asking questions. It must have been a terrible shock for her.

Apparently, my father had been to Douglas and was on his way home, on the main road coming through Onchan village. A large, open touring car came down from one of the side roads and ploughed straight into him. He was thrown off, which was, perhaps, just as well, since the car ended up on top of the bike.

Poor Daddy. He was not even unconscious but he had a double compound fracture of one leg, with a bone sticking out through the kneecap. He was always a calm person and even on that occasion remained so. When the ambulance arrived he took charge and himself directed the operation of conveying him to hospital.

His stay in hospital lasted four months and even when he came home he was for quite a time on crutches. He had had a plate inserted in his leg and was more than lucky not to lose the leg altogether. Financially, however, he was not so fortunate. The touring car housed seven young trippers - without any insurance. For the whole of his stay in hospital and even for some time after he came home, he was obliged to employ a locum to carry on the practice.

The locum, naturally, had to be housed and fed and paid a salary. This was of course, costly. It entailed as well, a great deal of work for my mother. She had to cope not only with the domestic side of things, but also with records and accounts and other jobs that my father himself would normally have attended to. She had to make sure there was always somebody in the house to take telephone calls; the locum had to be provided with lists of house calls to be made and she had to check that these were dealt with and not overlooked.

One could go on about all the little details in the daily life of a country practice in those days. It was certainly not all plain sailing. We had a number of different locums. One was a Londoner, an extremely nice man, but he could not stand the country life. He stayed only a fortnight.

In those days it was very difficult to persuade people that immunisation against diphtheria was a good thing. My uncle Charlie told me once that he had just the same difficulty in London and how upset he used to be over the unnecessary deaths which resulted.

Another locum we had was a young man, either too casual or not sufficiently knowledgeable, who failed to take a swab from a child who turned out to have diphtheria. The locum called at the hospital next day to make a routine report to my father who immediately sent him back to take the swab. Unfortunately, it was too late. The child died and the family blamed, not the locum, but his employer, my father.

By this time we had a car as well as Daddy's motorbike. Yet another locum took a girl for a spin up the mountain road in the car. Unfortunately he omitted to check that it had oil in it - and alas, the big end seized up. Somehow, I cannot help feeling that my parents must have breathed a huge sigh of relief when at length my father was able to resume work.

Putting all these accidents together makes it sound as if we had a permanent and constant casualty station. It was not so, of course. The accidents happened but, naturally not all together and not all the time. Things were often very prosaic and ordinary and life went on at a quiet country pace.

At one time Daddy dispensed his own medicines but this was time consuming and once there was a dispensing chemist in the village, Daddy simply made out the prescriptions for the chemist to dispense.

For quite a while too, having qualified in midwifery at the Rotunda in Dublin, he delivered many a baby in the district.

Eventually, a good maternity home opened in Douglas and he was happy to send expectant mothers there instead of, himself, delivering their babies at home.

It is a funny thing about babies. They often have an uncanny knack of making their first appearance in the night. I am sure that my father was indeed happy to hand over that side of medical practice to the maternity home.

Nevertheless, night calls were an inevitable part of a country doctor's work. This was particularly true of a scattered practice where there was only one doctor. If a call came it had to be answered, no matter what the circumstances.

Little Johnny might be screaming with pain and it might be something serious requiring immediate attention. On the other hand, little Johnny might have been scrumping and eaten too many green apples! You could never be sure in advance and you could never take chances.

This same code applied to every call. Too bad if you never got paid. Calls like that were what my father called 'God reward you jobs!'